The Italian Wars (1494-1559) were the cradle of the future Spanish famous unit, the Tercio. Initially called “coronelía”, it was shaped by the great war-master Gonzalo Fernandez de Cordoba “El Gran Capitán”. During these years, the power of the mobile fire guns, such as the arquebus and small cannons, became patent and changed the rules of war. This is one of my favorites periods of History, along with the following century. And taking advantage of some amazing 15mm miniatures I received from Khurasan Miniatures, I wanted to share with you this brief painting guide about how to paint bronze cannons. Remember that you also have this another painting guide about how to paint artillery of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), where I explained how to paint steel cannons.

The Italian Wars (1494-1559) were the cradle of the future Spanish famous unit, the Tercio. Initially called “coronelía”, it was shaped by the great war-master Gonzalo Fernandez de Cordoba “El Gran Capitán”. During these years, the power of the mobile fire guns, such as the arquebus and small cannons, became patent and changed the rules of war. This is one of my favorites periods of History, along with the following century. And taking advantage of some amazing 15mm miniatures I received from Khurasan Miniatures, I wanted to share with you this brief painting guide about how to paint bronze cannons. Remember that you also have this another painting guide about how to paint artillery of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), where I explained how to paint steel cannons.

The Italian Wars (1494-1559)

During the last years of the XV century and part of the XVI century, the Italian landscape was the witness of a series of conflicts denominated “Italian Wars”. The two main players involved in these fights were the Valois of France and the Habsburgs of Spain and Austria. By this time, the North part of Italy belonged to the Habsbrugs dinasty; and divided in several small states, the area was of vital importance to maintain open the “Camino español” (Spanish Road) and control the Burgundy and Flandes. In 1494 the French king Charles VIII invaded Italy with 25.000 soldiers, including a powerful siege train with around 40 cannons that demolished the walls of any city they encountered. Charles managed to capture Naples in 1495, which triggered the formation of an alliance, the Holy League, against the French invader. This was formed by the Holy Roman Empire, Milan, Venice and Spain. However, the coalition army was defeated by the French king in Seminara and Naples remained in French hands.

A few years later, under the leadership of the French king Louis XII, Genoa and Milan are captured in 1499. The Peace of Trent (1501) between Louis XII of France and Fernando II de Aragón supposed a brief halt in the war, with the subsequent partition of Naples. However, some discrepancies about the partition of Milan provoked the continuation of the war in 1502. This time, the French (and Swiss mercenaries) were finally defeated by the Spanish army -and the recently reformed units, “coronelía”- at the Garigliano River (1503). According to the Treaties of Blois (1504-1505), France lost Naples in return for controlling Milan. During these chaotic times, the city-state of Venice took advantage of the situation to expand their domains within Italy. To counteract this expansion, the Pope Julius II organized another coalition, the League of Cambrai. Although the “official” goal was to face the Ottoman threat, the real aim was to restrain Venice. However, Venice was defeated by a French army at Agnadello (1509) and the League of Cambrai was dismantled.

In 1512, a Swiss Confederation army arrived to the peninsula and captured Milan from the French. The same year, the French defeated a Spanish army in Ravenna, and one year later the Swiss took Lombardy from the French. The war escalated, and the new French King, Francis I, destroyed the Swiss army at Marignano (1515), gaining again the control of Milan and most part of Lombardy. The following year a treat of peace was signed between France and Spain, The Peace of Noyon (1516), which divided Italy between these two powers. However, the peace did not last for long. In 1519 the Emperor Charles V of Germany become also Charles I of Spain, merging the whole power of the Habsburg in a single person; and in 1521 the war in Italy started over again. In the following years the French army was defeated in the sonorous battles of La Bicocca (1522) and Pavia (1525). The French was expelled from Italy, as this was ratified by the Treaty of Madrid (1526).

However, Francis I did not give up and organized a new coalition against the Habsburg, the “League of Cognac”, composed by Florence, Venice, England and the Papal States. As a response, Charles V sent and army to Rome in 1527, which was sacked by the Spanish soldiers (“El saco de Roma”). Francis I tried to captured Naples, but failed. In 1529, the Ottoman reached Vienna (the first siege of Vienna) and Charles V reacted by sending troops to break the siege. This perhaps was part of a coordinated plan between the Ottoman Empire and France to beat down Charles V. However, it failed. France was definitely expelled from northern Italy, and this was reconfirmed in the Treaty of Cambrai (1529).

When the Duke of Milán die, Charles’ heir, Phillip (future Phillip II), obtained the duchy. France was not very happy about this, and Francis I invaded Saboya and captured Turin. However, Milan resisted the French attack. As a response, Charles (I) V invaded Provenza en 1536, but he decided to cease it and signed the Truce of Nice (1538). Turin remained in French hands. A few years later, Francis I tried again to invade Italy with the help of the Otomans. In 1542, a ottoman-french fleet surrender Nice, but the citadel resisted and one month later is liberated. In 1544, an Imperial army is defeated by the French at the Battle of Cerisoles (1544), but they were not able to invade Lombardy. To counteract the French actions, Charles (I) V signed an alliance with England and invaded the north part of France. However, the alliance did not work very well and Charles went back to Spain. The Italian borders did not change much.

Henry II followed Francis I in the French throne, and the war against the Habsburg started over again in 1547. France got the control of Lorena, but failed when trying to capture the Toscana in 1553; and a French army is severely defeated in the Battle of Marciano (1554). In 1556 Charles (I) V abdicated and Phillip II gained the control of the Spanish part of the Empire. The war in Italy would dramatically change after the Battle of San Quintin (1557), where the French is definitely defeated by Phillip II forces, and gave up to their rights over the Italian territories according to the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559). The “Italian Wars” finished, and the Spanish focus moved to Flandes.

The soldiers

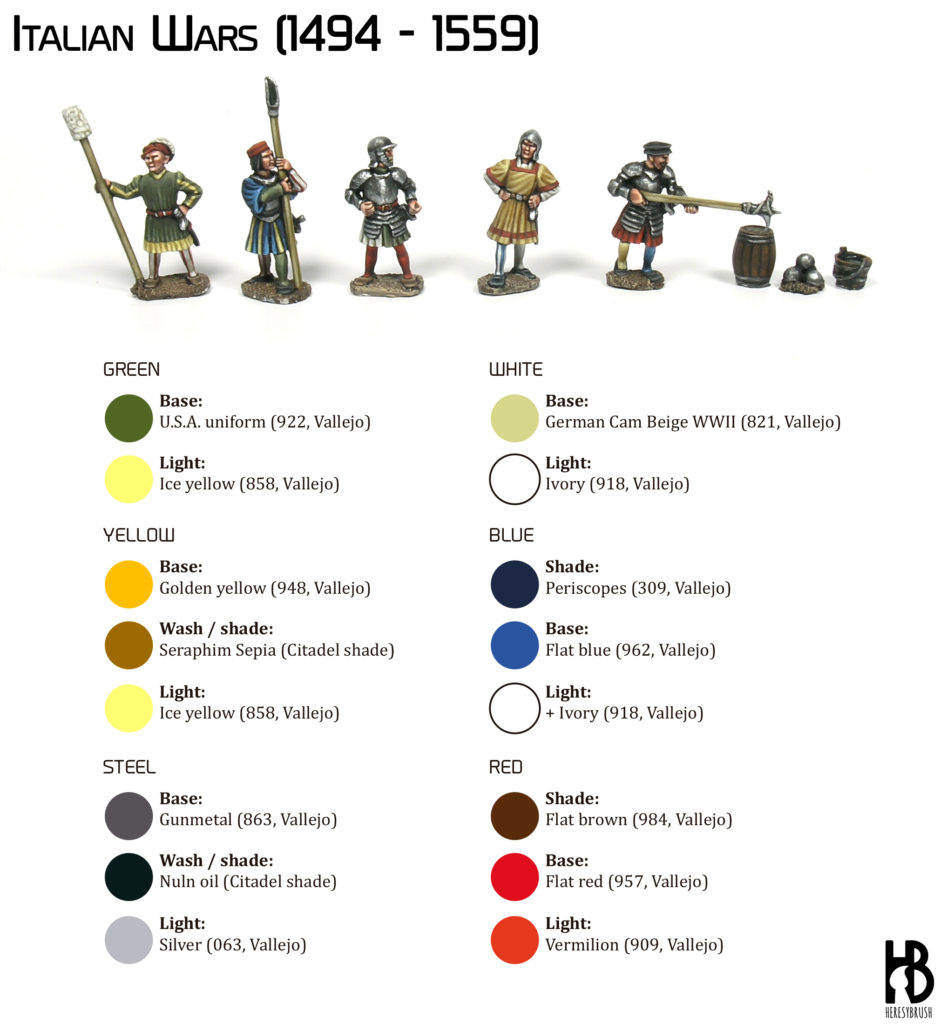

The armies of this period were very colorful as the renaissance also affect the military arms. It is important to note that the uniformity did not exist by then yet, and every soldier would wear its very particular clothes. Therefore, we can think about any possible combination of colors; and I encourage you to try to mix these in your units (check this for more information). Furthermore, I recommend you to check this amazing article about the gear used during the Italian Wars.

In the image below you can find a color chart containing the recipes I used to paint these miniatures. I would like to highlight a few things: (1) you can paint the stockings in the same miniature in different colors, for example one leg yellow and the other blue; (2) you can also paint stripes in the stockings in a different color, in one or both ; and (3) the gown could similarly be divided into two colors or have different decorations. Try to combine all these and do not repeat the same pattern. And of course, remember to check official references on the internet.

The bronze canon

First, assemble all the pieces and fix the with cianocrylate glue. Once it is dry, apply a primer coat with an airbrush or spray. I always use black primer when painting 15mm as I can always use it as a “black profiling” later on to separate different elements of the miniature, just by leaving a think black line between these.

Next, we paint the metal-fitting parts with Gunmetal (863, Vallejo) and the cannon with Bronze (057, Vallejo). Remember to dilute with water these colors too, but be sure that you have a different jar with water to clean the brushes. Acrylic metal paints leave many traces in the water, which can ruin the result of normal paints when using the same water to dilute these. To paint the wooden part you can use any brown color. In my case I chose a red brown, such as Cavalry brown (982, Vallejo).

To create some contrast in a quick and effective way we can use washes or shades from Citadel. I applied Nuln oil all around the cannon and the carriage. And once this was dry, I applied couple of layers of Agrax only on the bronze canon..

To highlight the metal parts I first recovered the original color using Gunmetal, and then applied a final highlight with Silver (062, Vallejo). I applied these lights on the edges of the metal-fitting parts. For the cannon, I did the same. But the final highlight was done with a 1:1 mix of Bronze and Silver.

Finally, we can simulate wood veins by painting horizontal lines with a lighter color and a thin brush.

>”by the Spanish army -and the recently reformed units, Tercios- at the Garigliano River (1503)”

Sorry, but “TERCIOS” as term and unit only showed up some 30 years later. Up the then, it was experimentation, with the Colunella in various compositions being shaped slowly – and in interaction with the Italian and German units that usually (well, always to some degree) fought beside the Spanish.

Good point! I got “lost in translation”, since in the Spanish version of the same post is correct.

Thank you very much for pointing it out! I will correct it accordingly.

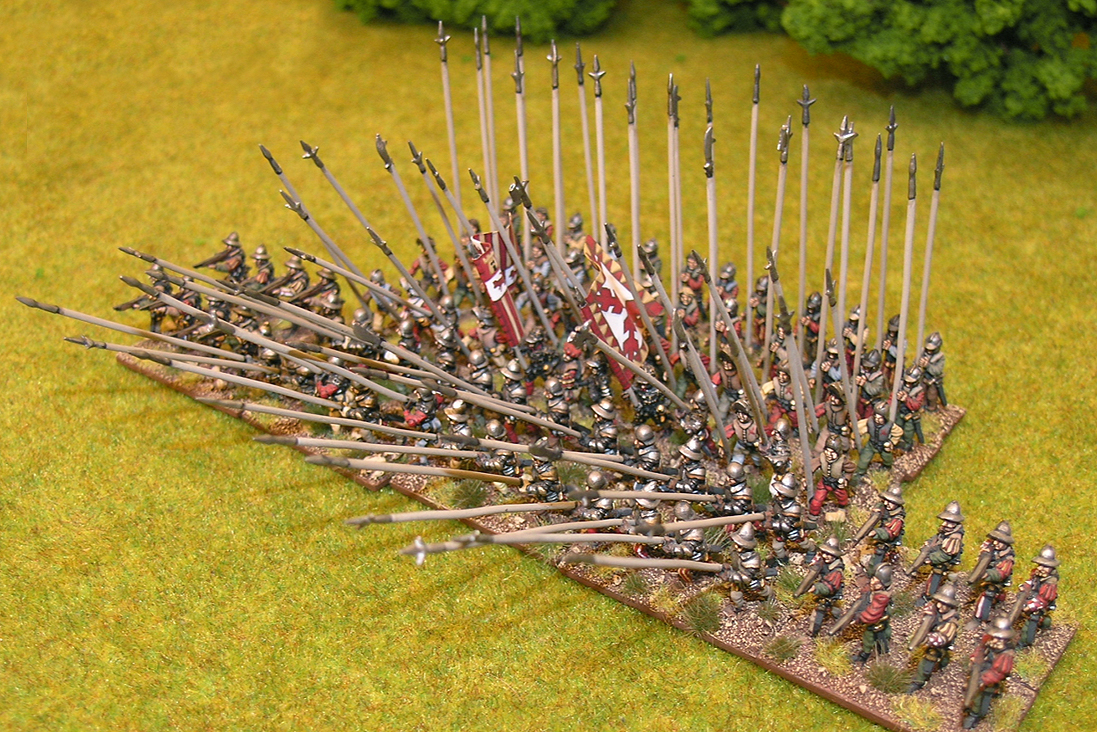

excellent painting and overview thank you, will you be doing a similar one for pike blocks ?

Thanks Nigel!

Actually, I did a similar article featuring two officers, which was published in Wargames: Soldiers and Stragety 76 (https://www.karwansaraypublishers.com/wss-issue-76-pdf.html). And I am also preparing a complete step by step guide explaining how to paint a whole tercio that will be hopefully publish soon in a book.

All the best,

R-